Share

Ernest Mwebaze, currently serving as the Executive Director of Sunbird AI, stands at the forefront of applying artificial intelligence to address pressing societal issues in Africa. Under his leadership, Sunbird AI, an organization stemming from the Makerere AI lab, focuses on developing impactful AI systems that target social good. From language technologies that support local startups and NGOs to collaborating with government ministries on projects like optimizing green mini-grids and analyzing social media data during the COVID pandemic. Mwebaze's commitment to responsible AI, transparency, and community involvement reflects a visionary approach to harnessing the power of technology for positive change in Africa.

Completing his primary and secondary education in Kampala, the capital city of Uganda, he emerged as one of Uganda's top 2000 students, earning the opportunity to pursue a tuition-free bachelor's degree in Engineering at Makerere University. This auspicious beginning laid the foundation for further academic achievements as he proceeded to attain a master's degree in Computer Science, followed by a journey to the Netherlands, where he earned a Ph.D. in Machine Learning from the University of Groningen. Dr. Mwebaze's education was marked by an alignment of dedication, talent, and opportunity, facilitating his studies and enabling his focus on advancing his skills in the rapidly evolving field of artificial intelligence.

The Africa I Know interviewed Dr. Ernest Mwebaze to learn more about his journey, his insights on leveraging AI for social impact, and commitment to advancing STEM education in Africa, as well as his advice for young Africans aspiring to make a positive impact in STEM fields, specifically in Data Science and AI.

Photo credit: Ernest Mwebaze

Photo credit: Ernest MwebazeI wanted the ability to create, and computer science seemed exciting for that, allowing me to do so using a computer.

Thank you very much for agreeing to do this interview with us. Can you please introduce yourself to our audience? What do you do?

Yeah, thanks a lot. I am called Ernest Mwabaze. I work as an Executive Director at Sunbird AI. I'm also on the board of Data Science Africa. These two profiles describe what I basically do. One is to try and apply practical machine learning solutions to societal problems, particularly in the context of Africa, and the other is to try and build capacity in data science and AI in the different communities in this context.

Can you give us an insight into your upbringing?

Yeah. So, I grew up in a family of six. I was the first boy, not the first born, but the first boy, second of six. Basically, I grew up in Uganda. All my education was in Uganda, apart from my PhD. My upbringing was fairly normal for someone living in Uganda, except when I was about seven years old, there was a war that brought in the current government. Apart from that, it has been a standard upbringing in an African country. I went to school here, went to university here, and then went for my graduate studies in Europe. Afterward, I came back here.

Can you tell us more about your education background?

I did seven years of my primary school here in Uganda, in Kampala, the capital city. So, I studied here for primary school. Then I went to secondary school for six years in a Catholic boarding school called St. Mary's College, also here in Uganda. After that, I pursued my bachelor's at Makerere University, where I studied Engineering. I continued with Computer Science for my master’s. Eventually, I completed a PhD in Machine Learning from the Netherlands, specifically at the University of Groningen. So, that's been my education path.

Did you have to pay for your studies? Did you have any financial burden on your education journey?

No, not really. I didn't have financial burdens. Well, my father may have had, but personally, I did not. When I finished secondary school to get to university, there was a program that sponsored the 2000 best students in the country, and I got into that program. So, I started engineering for free and then paid for my master's. The PhD was also a free program; I participated in the grants with Nuffic from the Netherlands. Luckily, I did not have to pay for that.

What inspired you to pursue your studies in Computer Science and Electrical Engineering, particularly in Artificial Intelligence?

Computer science has grown over time. Before, it wasn't a big thing; it was a small subset, similar to subjects like physics and chemistry. Even at that time, I really wanted to study computer science because I was excited about creating singularly using it. In most other fields, like engineering, creating requires tools, teams, and big things. In medicine, you can hardly create; you're mostly patching up and healing. While these are good things, I wanted the ability to create, and computer science seemed exciting for that, allowing me to do so using a computer while sitting down. That was the motivation for studying computer science.

I pursued engineering because at that time, computer science was not a standalone discipline. In Uganda, there was a small portion of computer science within electrical engineering, known as light current. So, I studied engineering, which turned out to be a good choice because much of it involves optimizing and building optimal solutions with scarce resources. This is crucial in creating and building things.

When I left that, AI became an embodiment of creation using computer science. It seemed the most likely path to create solutions that could address societal problems within our context. Those are my motivations.

There are people who believe in the “geek gene” hypothesis claiming people should have the 'natural talent' to excel in computing sciences. What are your thoughts on this?

I suppose you can understand why people would think that. If you look at a very limited set of people, maybe those who studied within your class or cohort, you may get the feeling that some have a different aptitude for these, and some don't, or some have an interest, and others don't. However, I suppose when you look at it in a wider population, you find that this may be fairly simplistic. I don't necessarily believe this. I think there are many factors, and we've seen that once people who thought these are not “for them” are given the opportunity, resources, and exposure, they excel drastically.

So, I don't entirely believe this. I think with the right opportunity, exposure, a bit of genetics, a disposition to mathematics, etc., people can excel in computing sciences. I think this hypothesis is a bit simplistic.

You are a founder of Sunbird AI and serve as the Executive Director. Can you please tell us more about the organization, its mission, and what inspired you to focus on practical AI applications for social good?

Sunbird AI has a history in what is now called the Makerere AI lab. I co-founded the lab, then named Data Science and AI lab, at Makerere University. The goal there was to apply computational tools to developing world problems. In a university setting, the goal is often curtailed by the need to create new academic research. Once a paper is published, that tends to be the end of the research. Sunbird AI was created as a continuation of that, focusing on taking something from being academically exciting to being practical.

The real focus was on building practical AI systems that target social good. After building a hypothesis and a proof of concept, the challenge is to make it practical. This is not a trivial task, and this is what we try to do. What does this mean? It means having a person interested in the solution, making it client-facing. After the client wants it, there are other practical considerations like deploying these solutions. Also, it could be that the solution to deploy is not at the bleeding edge of technology, but something simple that works on basic technology and machines easily.

The mission of Sunbird AI is to fill the space between academic research and practical considerations for instituting these applications within clients or people who need to use them, particularly targeting social good.

Can you share some of the practical AI applications that Sunbird AI is working on for social good, and how these applications are impacting communities in Uganda?

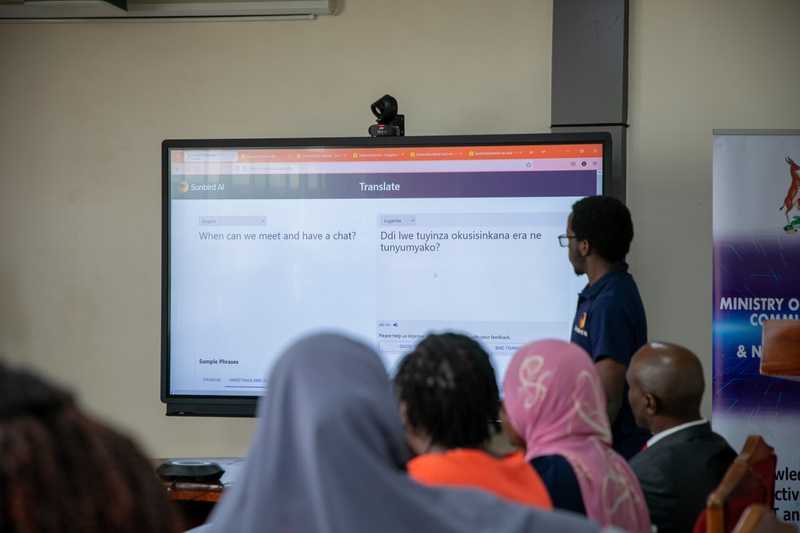

It's a very good question. Sunbird AI engages in two types of practical applications. One is to build base technology that can support practical applications in mass. An example project is developing African language technologies, which includes machine translation, speech synthesis, and automatic speech recognition models. We focus on low-resource languages in Uganda and aim to create language technologies for them. The practical outcome of this effort is that startups and NGOs can build off our technology. For instance, they can influence farmers who need to receive messages in a local language by using our APIs to send these messages. Startups building health apps also benefit by localizing content in our local languages through transcription and translation, reaching people in the health sector.

The second set of applications involves working on specific projects. For instance, we collaborated with the Ministry of Energy to develop a tool for identifying optimal locations for green mini-grids in Uganda. This entails finding the most suitable places, considering the entire country and people's educational and agricultural needs, to install a green mini-grid for power supply. This involves an optimization problem, and AI is employed for this purpose. We have also collaborated with the Ministry of Health on a project related to social media, aiming to understand public perceptions, particularly during COVID. Working with the Ministry of Health and the capacity authority, we analyze social media data to provide insights into the public's perceptions.

You also use AI to help support decision making and policy formulation. How does AI help in this, and why is this important for the development of Uganda and other African countries?

I guess the question is how to create sustainable change, sustainable social good. The way to do that, we believe, is through policies informed by evidence, and by evidence, we mean data. One way to achieve this is by using AI. AI has the ability to understand knowledge from large amounts of data. This is our approach to the theory of change in decision-making with AI. We use AI, particularly in situations where it is the optimal technology, which is in places with a lot of rapidly changing, difficult-to-analyze data. Social media data is an example—it involves a vast amount of data with many people talking in varied languages. How do you extract key insights and provide them to an organization to help them make decisions?

For instance, our social media project related to COVID was a clear example. We aimed to provide health information that assists in making practical decisions on the ground regarding how to address COVID. This is how we believe AI does it. It creates the evidence needed to support decision-making. If that evidence is robust, persistent, and constant, it can lead to policy formulation that supports sustainable social change.

But usually, AI systems are not interpretable; they're noted as black box models. So, if we really do not understand or cannot interpret their decisions, how are they going to help us in making decisions that will affect communities at large?

Right. Yeah, that's where things get a bit complicated, and building AI responsibly is extremely critical. That's where considerations like bias and people's privacy need to come in. So, it's always a careful balance that we have to strike. For example, at Sunbird AI, all our solutions are open source, as a policy. All the systems are open for auditing, and people can build upon them or inspect them if they have the technical know-how.

The second aspect is involving clients in the building process. Having the people who are going to use a system involved in building it is essential. It's easy to say but quite hard to do in practice, and I have to acknowledge that. However, we can strive to do things responsibly. In practical terms, this varies on a scale. For example, if you're trying to understand where to place green mini-grids and using satellite data, population data, and economic activity data, it's quite different from working on something in health, where you're trying to gather data and make predictions on health which we've done previously. So, we consider the practical aspects of the solution, the data involved, and ensure that we build things responsibly. We aim for transparency in decision-making, allowing audits of the systems to understand the decisions made, or at least ensuring that users have a fair understanding of what is happening in the system. Education in data science, even at a basic introductory level, is crucial, and we strive to incorporate that.

Glad that you mentioned AI bias. I would like to know your thoughts on the issue of AI bias and its potential impact on underrepresented communities, especially Africans? How can Africans actively contribute to mitigating AI bias and ensuring fair representation and outcomes in AI technologies?

Right, AI bias is definitely a serious issue. The importance lies in AI being trained on data. The more data you have, and the higher its quality, gives you a more faithful AI system. If that data is biased, you create systems that propagate this bias, posing a real challenge in building AI systems.

Unfortunately, AI bias works in two ways. Firstly, it can overshadow underrepresented communities if not represented in the data. This is a huge risk for Africans when discussing AI in Africa. Part of the reason we focus on language technologies is to ensure resources, especially technical language resources, enable the representation of underrepresented people, particularly in language. Secondly, bias can be propagated by the AI systems we build. This is crucial. A key thing is the idea of exposure. People need to be exposed to what their tools are doing, at least having a basic understanding of what AI is and what it's doing with their data. Once people have this, there's more accountability for their data to be represented, and for sound policies responding to responsible AI principles to be made.

In essence, addressing AI bias involves ensuring representative data for Africans and underrepresented populations in Africa. It also requires building technology responsibly. On the other side, there's the crucial education aspect. We aim to expose individuals to these systems so they can make informed decisions about their data, contributing to responsible AI practices.

How has your experience been leading Sunbird AI? What were your expectations? To what extent were your expectations met?

Setting up organizations is not easy. So, I think the principal expectation we had when setting up was that AI is at least understood fairly, and that people would be willing to try to harness the possibilities of AI. This was our assumption, but it was quite wrong. To convince people, especially public-facing organizations – which we are really interested in because that's where social good is most paramount – that this solution would be good for them or improve the way they do business, outcomes, and social benefit has been quite hard. We've had to build over time. These expectations we have to recalibrate and find ways to build relationships, ensuring that people can hopefully understand what we're trying to do and engage in it.

What was the hardest hurdle you encountered in your career? How did you overcome it?

I think the hardest hurdle has really been to try and convince people, even when the solution seems a bit clear in your head, to convince people that the integration of a practical AI system would be beneficial to their work, business, or society. This has been quite hard. Conversely, convincing people to support that solution has also been challenging. We are nonprofit, so we work with donors and the government to ensure that they can support these systems. This has been quite hard.

What are important lessons you've learned on your way to where you are now in your career?

One is to have a strategy or philosophy for your career that surpasses the normal considerations. You want to be paid well and satisfied, but having a philosophy outside your career is crucial. For me, it's been trying to influence the context I live in to tackle the significant societal problems facing the African context. This has had a positive effect on my career.

The second lesson is the trade-off between exploitation and exploration, related to change. Change is beneficial, but when and how to change is a learning curve. The lesson is that there has to be a mix between exploitation, making the most of current opportunities, and exploration, venturing into new fields, careers, options, and organizations. Striking the right balance is key for advancing your career.

What are you most proud of?

Well, I think I am most proud of the community. When we started this work, very few people were interested in computational means, specifically machine learning and AI, to help solve community problems. But we've grown through initiatives like Data Science Africa and built a large community of people interested in data science, machine learning, and AI. People have built careers from this community, moving to different organizations and achieving remarkable things. So, the growth in this community of people interested in using data science to influence their communities is the thing I'm most proud of.

Looking back on your journey, is there anything you would have done differently or any advice you would give to your younger self?

This is a tough one. I think I could have explored more, switched things up a bit, and been less risk-averse. Maybe I could have learned more about different things. So, I feel I was a bit conservative in some of the choices I made.

What are your thoughts on Africa? What do you think are the biggest challenges facing the continent?

Maybe, I have two perspectives on this. One is the structural problems with Africa. Africa was colonized, and the first country that got independence was Ghana in 1957. So, if you look at the period from 1957 to now, roughly 70 years of “development” or “progress.” One aspect is that we are young in many ways, particularly in appreciation of education, technology, and government, especially leadership. Compared to civilizations with a history of 400 years, like the US, there's a structural gap.

The other perspective, which is more practical, involves challenges in areas like education and infrastructure such as the Internet, roads, education, and health systems, making technological progress difficult when these foundational aspects are broken. These are the significant challenges. Then, of course, we have challenges that ride over these, such as the capacity in Africa to do AI. We have limited capacity in universities and among people with the necessary skills. The capacity is limited both in depth and breadth, both in the expertise of individuals and the number of people possessing these skills.

In your opinion, why do you think people of African descent are underrepresented in STEM fields? What do you think should be done to motivate more people to get into STEM?

One, I guess it's just the age, where Africa is fairly young in terms of civilization. People have been studying physics, chemistry, and the sciences for a long time, and we have onboarded fairly recently. So, that would mean that people are generally fewer, but I think there are also cultural factors. We have somewhat different cultural ideologies, such as certain beliefs that restrict women from going to school or doing math. Over time, we have been overriding these cultural barriers. This means that we are underrepresented in things like STEM.

So, what can be done to motivate? I think a lot of action is happening, particularly to put emphasis on exposure in education. Education is one of the key things that we need to get right. It involves exposure to these technologies and subjects at global levels, so people have a good appreciation of these subjects, especially exposure in practical aspects that they can relate to in their context. This is important for people to appreciate STEM more because it relates to their context, and they can engage with it meaningfully.

In your experience, what are the main skills and qualities that young Africans should develop to excel in STEM fields and make a difference in their communities?

So, I think the key one is problem-solving skills. I know it's a standard term, but it's crucial for young Africans. What does that mean? Problem-solving skills entail having the right technological knowledge, a background in math, and programming skills. Programming has become very accessible now with online courses, and there's an abundance of resources and exposure for young Africans to engage in larger discussions by taking advantage of these technologies and open education.

If they have problem-solving skills, it means they can discern which skills to focus on, harnessing online resources. The idea is to assess their context and determine which problems are most likely to benefit from their current skills. We call this End-to-End Skills in our Data Science Africa initiative. I think these would be the main skills and qualities that young Africans would benefit most from to engage in STEM.

What is something that someone wouldn't know by looking at your profile? Any fun facts?

[Laughs] Well, they wouldn't know if I have a lot of hair or no hair at all [laughs]. I like to dance, just like the next African guy. Maybe someone will know that. Maybe not.

Finally, what words of encouragement or advice would you give to young Africans who are passionate about STEM and want to make a positive impact on their communities and the world?

It's, I think, to delve into communities, especially if they're passionate about STEM. Join the communities that are trying to do something with STEM in their areas. I know there are many organizations and communities here in Africa, such as Data Science Africa, Deep Learning Indaba, PyLadies, etc.

These niche communities consist of enthusiasts and people working, for example, on data science, aiming to make an impact in their communities. I've found the largest encouragement and drive, especially in this field, comes from having a community outlook. How can the skills and technologies they're trying to acquire be used to benefit the communities they live in? I think this is a mission or goal that you can never fully exhaust; it keeps driving you forward. These would be the words of encouragement I would give them.

Know someone we should feature? Or are you of African descent and would you like to share your journey with us? Email us at editors@theafricaiknow.org

Our Newsletter

Subscribe to our newsletter to keep up with our programs and activities, learn about exciting developments in Africa, and discover insightful stories from our continent's history.