Share

From a crowdfunded technology innovation aiming to help rural hospitals and clinics in Cameroon to an award-winning internationally distributed medical device, the CardioPad promises to democratize cardiovascular healthcare access to the most vulnerable.

Arthur Zang, a Cameroonian inventor, lost an uncle due to cardiovascular disease, and he decided to use that as motivation for his invention. It might surprise you to learn that cardiovascular diseases are the number one cause of death in the world. In 2017 alone, 17.8 million people died at the hands of this single killer. Cancers are runners up, causing up to 9.6 million deaths, nearly 50% lower than cardiovascular diseases. More than 75% of cardiovascular-related deaths occur in low-and middle-income countries.

These numbers hit home. About 12% of deaths in Cameroon are related to heart disease. Made worse, this Central African nation with a population of roughly 22 million, only has about 30-50 heart specialists in the entire country. By comparison, the United States, with a population of 330 million, has about 33,000 cardiologists (3 orders of magnitude more than Cameroon). How can roughly 50 specialists be responsible for an entire country? There indeed had to be a way to surmount these daunting odds.

Training the requisite number of specialists would require longer time scales, institutional changes, and high economic costs - amongst other impediments. What if there was a way to scale one heart specialist to reach many more patients regardless of where they are?

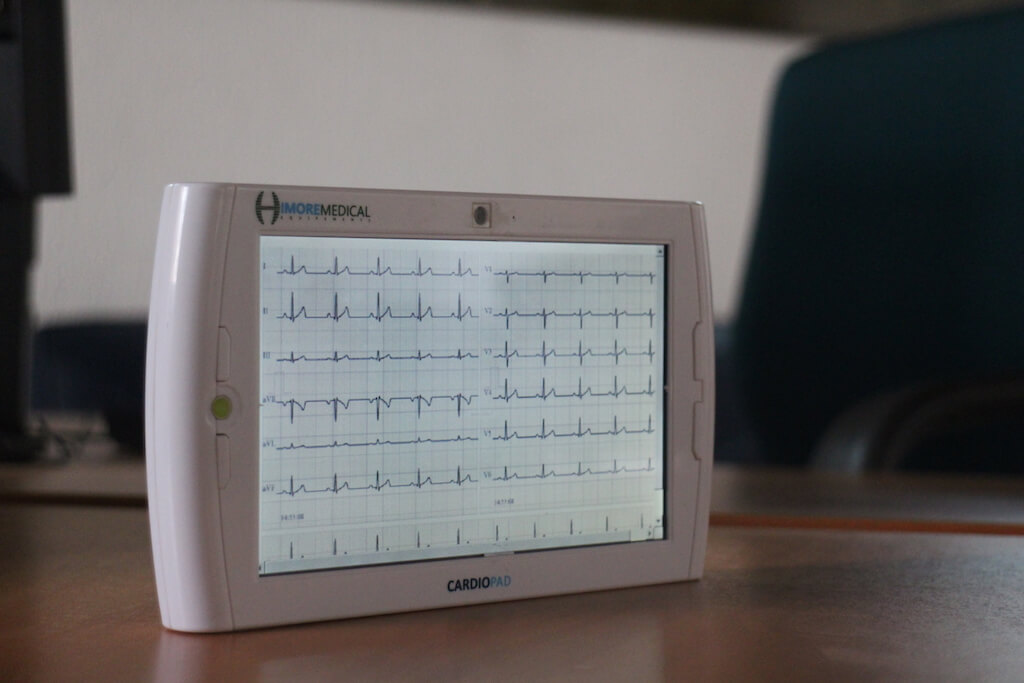

The battery-powered touchscreen CardioPad with patient readings. Photo credit: Himore Medical

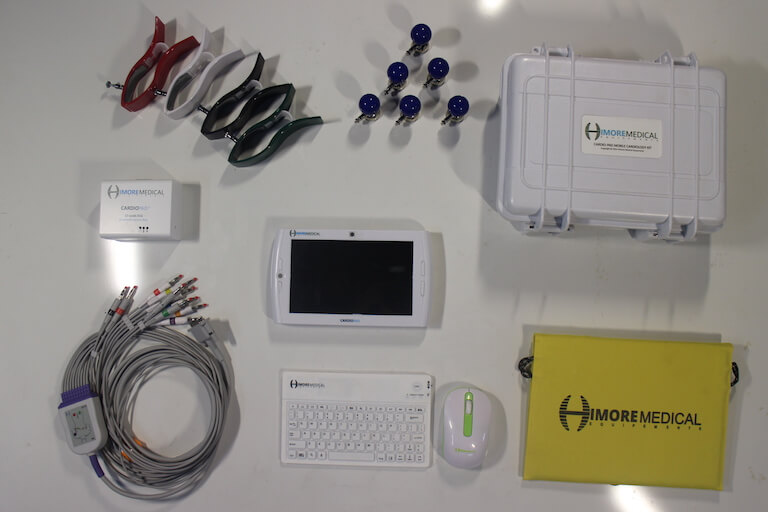

Enter the Cardiopad. Arthur Zang invented the Cardiopad to allow heart specialists to consult on multiple patients regardless of where they are in the country. The Cardiopad functions as an electrocardiograph, which measures electrical signals from the heart derived from attaching electrodes on the skin. For someone in need of cardiovascular care, but lives in a rural area, they would pay a visit to their local clinic or hospital. Suppose this rural hospital has purchased a Cardiopad. In that case, it makes this visit much more efficient because the Cardiopad is a portable medical tablet used to perform examinations and record patient data. The patient would have electrodes attached to them and connected to a battery-powered, handheld tablet for assessing cardiovascular health via patient electrical readouts. The clinic transmits the patient's data from the Cardiopad via a mobile phone connection to a National Data Center in the cloud for storage. The cardiologist, who likely resides in a city, can now retrieve the health record. Upon the interpretation of the patient's medical data, they can make a diagnosis and send over their direction and annotations back to the patient's hospital. Our patient's rural hospital or clinic can provide follow-ups on the requisite care.

A CardioPad kit including electrodes and cables for patient data collection. Photo credit: Himore Medical

The CardioPad prevents the long-distance, time-consuming, and costly trips patients would otherwise make for a cardiologist visit. Patients can now make trips only when required. It eases the burden on the patients, cardiologists, and the medical system.

Arthur's Himore Medical company fabricates these patented touchscreen CardioPad prototypes. Launched in 2016, the CardioPad costs roughly $3000 per unit at this stage of early production. The business model works by having patients subscribe at $29 yearly to CardioPad services through their clinics. There have already been sales of Cardiopads in a few countries, including Gabon, Cameroon, Nepal, and India.

The CardioPad is an African invention with great potential to impact the world and bring higher quality healthcare to patients suffering from cardiovascular diseases.

Would you like to submit an article to us? Contact us at editors@theafricaiknow.org

Our Newsletter

Subscribe to our newsletter to keep up with our programs and activities, learn about exciting developments in Africa, and discover insightful stories from our continent's history.