Share

When I was growing up as a science student in Tanzania, I wondered if there was any theory named after an African. I recall how fond we were of nicknaming ourselves after some famous European scientists. Until today we still call one of our classmates Schrödinger, the name of the Nobel Prize winner in Physics. It was so fascinating to learn about the likes of Amadeo Avogadro, Blaise Pascal, Daniel Bernoulli, and many other white men whose findings are named after them.

So, you would understand why it was quite a sweet revelation many years later when I came to realize there is actually something scientific named after someone from my home country. His name is Erasto Mpemba. At that time there were not many articles written about him and we spent our time debating on social media on whether his findings meant a lot to the scientific community.

Now when you google his name many journal articles pop up on the effect that is named after him. As I write this article, Google scholar yields 520 results when you search "Mpemba Effect." My interest is not to repeat what you can read out there, but rather to take you back to the beginning for a reflective journey on what it took for such effect to be named after a secondary school student.

The year was 1963, two years since Tanganyika gained its independence and a year before it had joined with Zanzibar to form the United Republic of Tanzania. Mpemba was a Form 3 student at Magamba Secondary School in what is now known as the Tanzanian region of Tanga. Like some of us who encountered a refrigerator later in our childhood, he used one to make ice-cream. In his case, he used to boil milk mixed with sugar and let it cool before putting it in the freezer of their school's refrigerator. However, one day things did not go as planned. Another boy outran him to the refrigerator when he saw Mpemba "boiling up milk." This other boy "quickly mixed his milk with sugar and poured it into the ice-tray without boiling it; so that he may not miss his chance."

Guess what Mpemba did? "Knowing that if I waited for the boiled milk to cool before placing it in the refrigerator I would lose the last available ice-tray," he recalled six years later, "I decided to risk ruin to the refrigerator on that day by putting hot milk into it." When they both came back "an hour and a half later", they found thatMbempa's tray of milk had frozen into ice-cream while that of the other boy "was still only a thick liquid, not yet frozen." But his Eureka moment was soon scorned.

It seems no one in his school could believe that a student – and an African one for that matter – could make such a 'discovery' somewhere in Africa. "I asked my physics teacher why it happened like that, with the milk that was hot freezing first, and the answer he gave me was that 'You were confused, that cannot happen," Mpemba recalledlater. "Then", he further recalled, "I believed his answer." That was a lost opportunity to nurture his inquisitiveness and mentor him on the matter.

Mpemba did not entirely give up. When other opportunities came up, he seized them. The first one was during his school break when he met a cook in Tanga town who also made and sold ice-cream. He was intrigued to learn that the cook's brother had taught him how to make more ice-creams faster by doing what Mpemba did incidentally in school. This encounter is particularly important as it continued to nurture the seed of curiosity in him. It also reminds us that some of the scientific knowledge named after particular individuals were collective knowledge shared in communities.

A second opportunity came when he became a student at the then Mkwawa High School in the Tanzanian region of Iringa. "One day as our teacher taught us about Newton's law of cooling," he recalls, "I asked him the question, 'Please, sir, why is it that when you put both hot milk and cold milk into a refrigerator at the same time, the hot milk freezes first?'" But the "teacher replied: 'I do not think so, Mpemba.'" He "continued: 'It is true, sir, I have done it myself.'" But his teacher said: "'The answer I can give is that you were confused."" One can only imagine his frustrations.

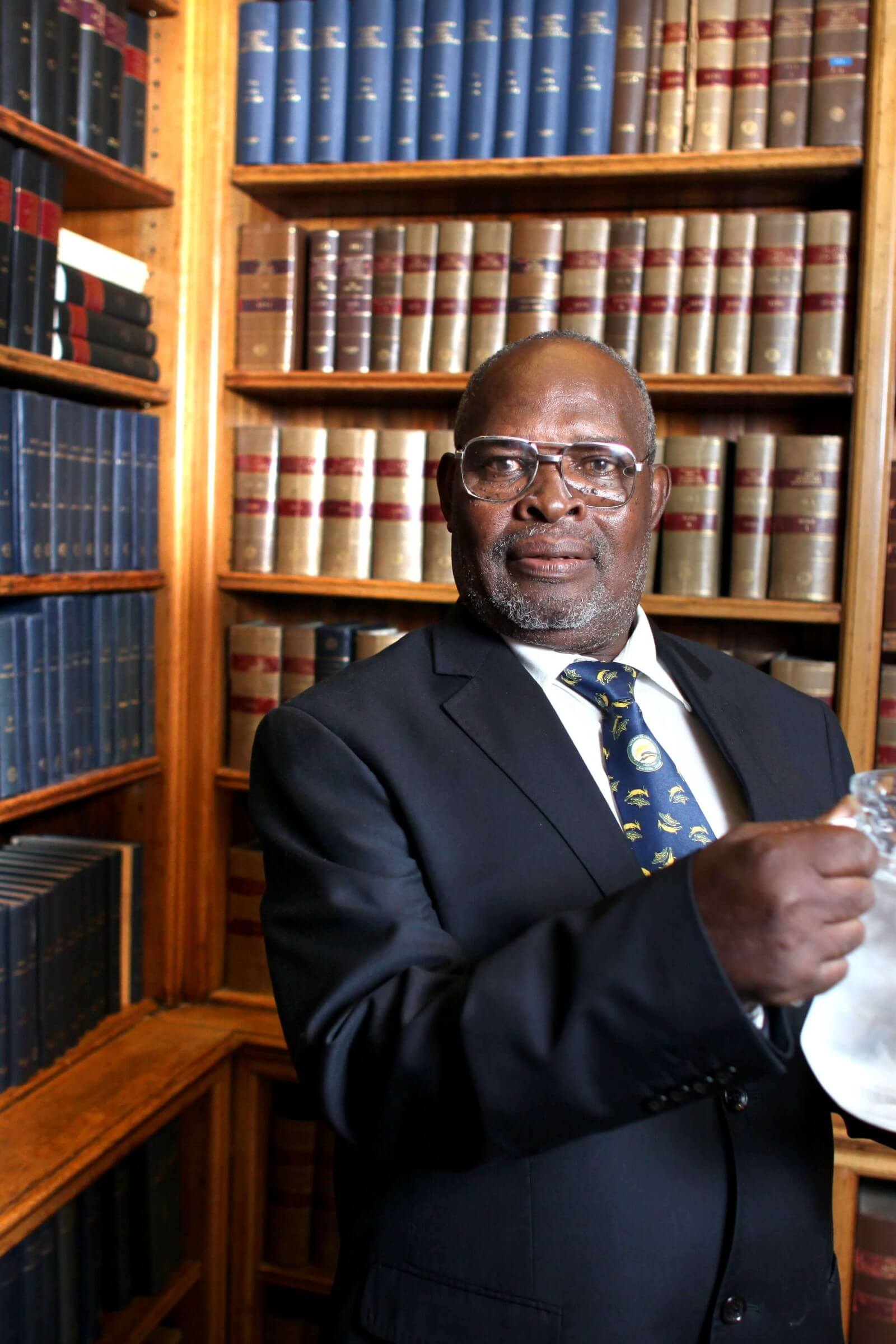

_Erasto Mpemba at a presentation in London_

_Erasto Mpemba at a presentation in London_

Yet Mpemba "kept on arguing, and the final answer" he gave him was that: "'Well, all I can say is that that is Mpemba's physics and not the universal physics.'" As if this discouraging form of pedagogical bullying was not enough, a whole new name calling came out of this teacher-student imbalanced power relations. "From then onwards", he recalled, "If I failed in a problem by making a mistake this teacher used to say: 'That is Mpemba's mathematics.'"

Fortunately, after doing his own experiment in the biology laboratory, the third opportunity turned things around. This was when Dr Dennis Osborne from the then University College Dar es Salaam visited their school and they were allowed to ask him questions. Mpemba asked why if "you take two similar containers with equal volumes of water, one at 35 °C and the other at 100°C, and put them into a refrigerator, the one that started at 100 °C freezes first". Unlike, his physics teachers, the visiting scholar treated him as a scientist by asking: "Is it true, have you done it?" He said, yes.

After acknowledging he did not know why, the visitor promised to try the experiment when he gets back to Dar es Salaam. So began a collaborative effort that resulted in the publication of this seminal article: Mpemba, Erasto B., and Denis G. Osborne. "Cool?" Physics Education 4.3 (1969): 172. It took a lot of guts for Mpemba to weather the ridicule from some of his fellow students who said he did not understand his chapter on Newton's law of cooling. His courage finally paid off.

For those who are still wondering what does the "Mpemba Effect" actually mean even after reading his own version of the story as retold herein, be as curious as him. It simply means that, contrary to what is generally perceived to be the case, at a certain level of temperature, hot water actually cools off quicker – and thus freezes faster – than cold water. This is indeed a puzzling phenomenon. No wonder in 2015 one Yale university student was still referring to it as an "Unresolved Mystery."

Erasto Mpemba's story ought to be taught and publicized widely to inspire all young Africans who are aspiring to be trailblazing scientists. What was made fun of as Mpemba's physics and mathematics has now become the scientifically recognized Mpemba Effect. His dream was valid.

Would you like to submit an article to us? Contact us at editors@theafricaiknow.org

Our Newsletter

Subscribe to our newsletter to keep up with our programs and activities, learn about exciting developments in Africa, and discover insightful stories from our continent's history.